Bukharan Jews are believed to have settled in Central Asia as early as the 6th century, with solid evidence of their presence from the 4th century CE. Initially part of a broader Judeo-Persian community, they lived in cities like Merv, Samarkand, and Bukhara.

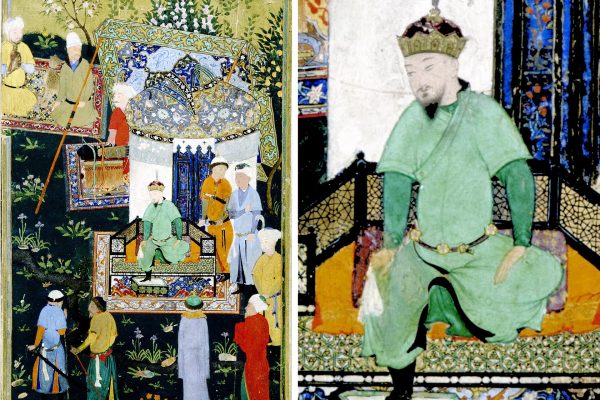

During Timur’s 14th-century reign, Bukharan Jews contributed significantly to Central Asia’s reconstruction, especially in weaving and dyeing. They later came to dominate the region’s textile and dye industry.

In the 16th century, religious and political divisions between Shia Iran and Sunni Central Asia split the Jewish communities, creating a distinct Bukharan Jewish identity. A similar separation occurred with Afghan Jews in the 18th century, though migration between regions still occurred.

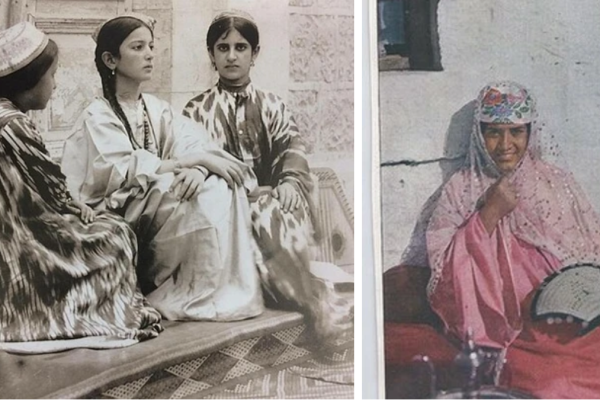

Bukharan Jews lived under discriminatory Dhimmi laws, facing persecution and forced conversions, with strict dress codes and social restrictions. Despite oppression, they thrived as merchants and were confined to a Jewish quarter called the Mahalla.

In 1793, Rabbi Yosef Maimon arrived in Bukhara and enforced Sephardic traditions, replacing local Persian customs, which revived but also divided the community. His descendants, like Shimon Hakham, promoted education and religious literature in the Bukhori language.

Russian rule (1865–1916) marked a "Golden Age" for Bukharan Jews, granting them equal rights and allowing prosperity in trade, arts, and professions. Many migrated to Ottoman Palestine, founding Jerusalem’s affluent Bukharan Quarter, though it later declined post-WWI until efforts revived it in the late 20th century.

Starting in 1872, Bukharan Jews moved to Ottoman Palestine, founding Jerusalem's Bukharan Quarter—an affluent neighborhood with European-style architecture and vibrant Jewish life. After WWI and the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the area declined, but later revitalization efforts in the 1980s restored it. Today, it remains home to mostly Haredi Jews.

Under Soviet rule, Bukharan Jews faced religious suppression, forced assimilation, and mass arrests during Stalin’s purges, prompting many to flee to Iran, Afghanistan, and Palestine. Despite intense pressure, the community struggled to maintain traditions while enduring antisemitic and anti-religious campaigns, especially after 1948 and the 1967 Arab-Israeli War.

Bukharan and Ashkenazi Jews in Central Asia remained mostly separate, with minimal intermarriage and differing religious practices. However, Bukharan Jews had a longstanding, positive relationship with Chabad-Lubavitch, who supported their religious needs, and Jews from other Eastern communities were absorbed into Bukharan Jewry over time.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, nearly all of the 50,000 Bukharan Jews in Central Asia emigrated to the U.S., Israel, and other countries due to economic instability and rising nationalism. Riots and threats in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan pushed the remaining Jews to leave in the final major wave of emigration.